Who Owns Our Knowledge?

Copyright, Gatekeeping, and the Fight for Access

I’m not always going to write about Copyright stuff, I promise. But I’ve been sharing the OLL with more folks and I keep getting reminded how much the current regime of copyright tends to keep knowledge out of the hands of our Community members.

When I started building the O'odham Learning Library, I ran into a problem I never expected to make me so angry: copyright law.

It wasn’t that I didn’t understand it—of course I knew copyright existed. It protects artists, writers, and researchers, making sure they get paid for their work. That makes sense to me. If you put in the time, effort, and creativity to produce something, you should benefit from it. But that’s not what happens most of the time, is it?

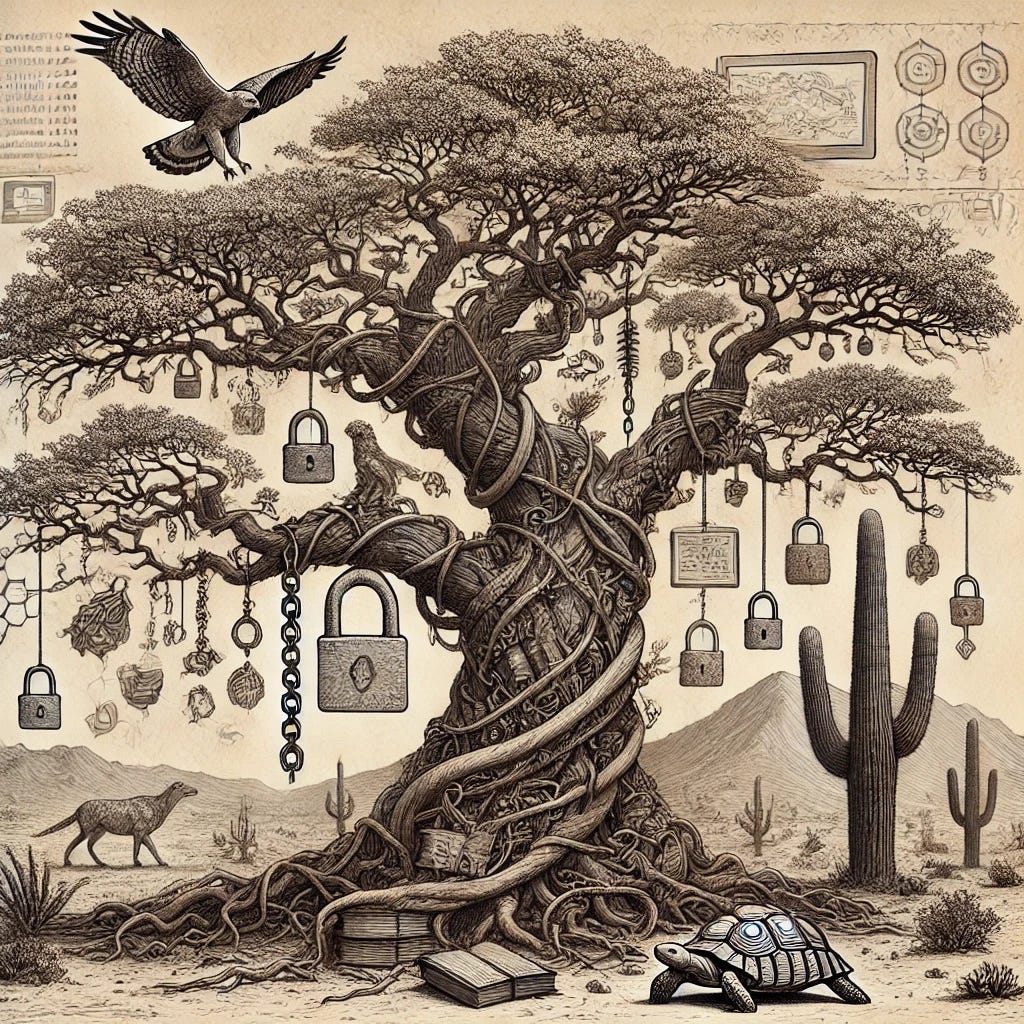

In the world of academic publishing, knowledge is often extracted from Indigenous communities, written up in a book or article, and then locked behind a paywall that our own people can’t afford to access. An anthropologist spends time interviewing elders, taking notes on our stories, our history, our ways of life. They publish their findings, add a copyright symbol, and suddenly our knowledge belongs to someone else.

And the kicker? If we want to read it, we have to pay.

Who Benefits from Copyright?

I want to be clear: I don’t have a problem with academics studying our communities. In fact, I appreciate those who take the time to document our histories, who dedicate their lives to understanding and preserving Indigenous knowledge. But the way copyright works right now? It doesn’t benefit those researchers—it benefits publishers. It benefits institutions. And it actively works against the very people whose knowledge is being written about.

One of the core tenets of Fair Use is that a reproduction of a work shouldn’t reduce its commercial value. But who else is buying these books? Who else wants to read about our creation stories, our basket-making traditions, or the biographies of our elders? More often than not, it’s our own community members who are trying to access this knowledge. The knowledge that was taken from us.

Meanwhile, academics and institutions have privileges we don’t. They have university credentials that let them download articles from expensive databases. They have grant money to purchase books. Our people, on the other hand? We’re told we need to pay out of pocket—if we can even find these materials in the first place.

A System Designed to Exclude

I have spent years building the O’odham Learning Library, trying to make sure our community has access to materials that are rightfully ours. And still, I have to carefully navigate copyright law. I have to worry about DMCA takedown requests. I have to structure public and private access in a way that minimizes (but never eliminates) the legal risks.

That shouldn’t be the case.

Right now, the law serves publishers, not communities. It locks knowledge away unless you have money or institutional affiliation. And in many cases, the copyright isn’t even held by the person who wrote the work—it’s held by the publishing company. The researcher who spent years studying our history? They’re not the ones profiting from these restrictions. The publisher is.

A Call for Change

Copyright law needs to change. And not just in ways that benefit corporations or elite institutions. We need carveouts for Indigenous communities, for historically marginalized groups, for people whose knowledge has been taken and commodified by others.

We need laws that prioritize access over profit. That recognize knowledge as something living, something communal, something that can’t be locked away by a publisher’s copyright claim.

For now, I work within the boundaries of Fair Use because I have to. Because I don’t want to risk the OLL being shut down. But let me be clear: It is absurd that I even have to worry about that.

With AI and other technologies pushing the boundaries of copyright law, we have a moment—an opportunity—to rethink the entire system. We can fight for changes that benefit all communities, not just those with money and institutional power.

Because at the end of the day, our knowledge belongs to us. Not to publishers. Not to institutions. Not to copyright lawyers.

And I, for one, am tired of asking for permission to access what is already ours.