Luis Morago - Luis the Interpreter

The Story of an O’odham Interpreter, Scout, Leader

Made with help from ChatGPT’s Deep Research model. Edited and fact-checked by me. I always recommend talking to an elder or knowledge keeper to learn more.

I have a version that includes footnotes and citations if that is your jam - you can find it HERE

Big props to Billy Allen for doing so much amazing research. His GRIN columns helped me to find sources for a lot of this information!

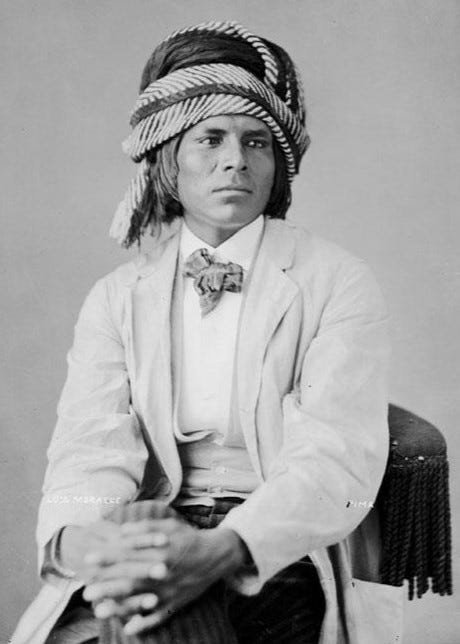

Alex Gardner photograph of Luis Morago, 1872.

Introduction

Luis Morago (also recorded as Luis Morajo or Luig Morague) was an Akimel O’odham interpreter and scout from our Gila River Indian Community in the late 1800s. He bridged cultures at a critical time. Morago is remembered for his fearless service during the Apache conflicts of the 1860s, for helping bring a fragile peace after the Camp Grant Massacre, for interpreting on a historic 1872 delegation to Washington, D.C., and for his role in our early irrigation efforts. This is a short biography based on some of the more well known moments in his life.

Early Life

Luis Morago was born into the O’odham world at a time before our people were split by reservation lines. According to later notes, he was actually Tohono O’odham (Papago) by birth, yet he came to live among the Akimel O’odham (Pima) of the Gila River. In joining our Gila River community, Morago married an Akimel O’otham woman and made this his home. By the 1860s, he was known as a fluent speaker of O’otham and English – talents that would soon prove invaluable. In November 1869, the U.S. Indian agent at the Pima Agency formally hired Morago as the agency interpreter. (The agent’s letters reveal he had first tried a man named John D. Walker as interpreter, but then turned to Morago as a better fit.)

From that point forward, Morago was our community’s voice in dealings with outsiders. He helped teach our language and culture to newcomers like missionary-teacher Charles Cook, who arrived in late 1870 – Cook “learned O’otham from Louis Morago” before opening our first school in 1871.

Apache Conflicts of the 1860s

Morago came of age during an era of intense conflict between O’odham and Apache. Our people had defended our river valley from Apache raiders for generations before him. By the 1860s – as the United States took control of Arizona – the longstanding war with the Apache was at its peak. The U.S. military began recruiting O’odham scouts to help fight their campaigns, recognizing what we already knew: no one knew the enemy’s moves or the desert trails better than us.

Morago emerged as one of those indispensable scouts and leaders. Written sources later honor him as an “Apache Wars hero of the 1860s”. One of Morago’s sons (who later became a tribal police captain) described his father as “an Apache Wars hero” as well when petitioning the government for our rights.

This status was earned through blood and danger. The 1860s had been a brutal decade – but Morago helped our people survive it by keeping the enemy at bay and maintaining an alliance with the U.S. Army.

We know Pima scouts participated in U.S. expeditions against the Apache throughout that decade. It is very likely Morago took part in several such campaigns as a guide and translator for the U.S. Army. Our O’odham scouts tracked Apache bands across the Superstition Mountains and San Carlos country, often engaging in skirmishes at close quarters. Morago and other O’odham scouts helped blunt Apache incursions that threatened our families. The United States, for its part, was grateful for the critical intelligence and desert survival skills we provided.

Camp Grant Massacre and the Peace of 1872

The violence between Apaches and settlers reached a horrific climax on April 30, 1871, in an event that shook all of Arizona. In the pre-dawn darkness, a mixed posse of 6 Milgahn, 48 Mexicans from Tucson, and 98 O’odham warriors from San Xavier (Tohono O’odham) attacked an Apache camp at Arivaipa Canyon, near Camp Grant.

Over 100 Apache women and children were killed in less than 30 minutes, and 27 Apache children were kidnapped during the onslaught. This atrocity, known as the Camp Grant Massacre, filled our community with grief and confusion. While no Akimal O’otham took part in the raid, some of our Tohono O’odham cousins did – spurred by longstanding feuds and recent Apache raids on their villages

The massacre horrified U.S. officials: President Ulysses S. Grant himself demanded justice and an end to the cycle of vengeance. Yet when the Tucson perpetrators were put on trial, a local jury acquitted them in just 19 minutes. Apaches had been slaughtered without legal consequence, deepening their bitterness and despair.

In the wake of the massacre, General Oliver O. Howard was sent as a peace commissioner to Arizona. He understood that without peace, all-out war would continue between Apaches, O’odham, and the milgahn settlers in the area. In May 1872, Howard convened an extraordinary Peace Conference at Camp Grant – a face-to-face meeting of Apache leaders, O’odham leaders, and U.S. authorities.

From our side, Chief Antonio Azul led the Gila River delegation, accompanied by 12 village headmen and Indian Agent J. H. Stout – and they brought Louis Morago as their interpreter. Fifteen Tohono O’odham (Papago) from San Xavier also arrived, including two of their headmen. The Apaches, led by chiefs including Eskiminzin of the Arivaipa and a chief named Santos, came to talk instead of fight. It was an unprecedented gathering.

On the first morning of the talks, as both sides mingled warily, an Apache man suddenly approached our group and pointed at Morago. In a startling moment of recognition, he exclaimed: “You’re the Pima who killed me years ago!”. Everyone froze. It turned out this Apache had been a warrior whom Morago knocked out with his ironwood club in a skirmish years prior – left for dead, but he lived to remember the face of his attacker.

Now, instead of renewing the fight, the Apache greeted Morago happily; he was almost relieved to see that formidable Pima warrior again under flags of truce. This tense but oddly cordial encounter set the tone: old enemies would set aside grudges. As one observer noted, “Old wounds do heal after all”. Morago’s presence – symbolizing every bloody O’odham-Apache clash of the past – became a powerful reminder of why peace was needed.

With Morago interpreting each speech in O’otham and English, the conference proceeded. General Howard and General George Crook sat listening as first the O’odham spoke, then the Apaches. In one dramatic gesture, Apache Chief Santos laid a large rock on the ground and declared, “I want a peace that will last as long as that stone lasts.”.

In response, our leader Azul recalled that long ago, the O’odham and Apache “were all one people living in peace.” Now, he said, “we are friends again… and I am satisfied we will remain friends.” Another Papago headman, Francisco, agreed: “The stone has been placed before us as a symbol of peace.”

From that year forward, never again would large-scale war erupt between our two peoples.

The 1872 Delegation to Washington, D.C.

Only weeks after the Camp Grant peace council, Luis Morago took on a new mission: traveling across the country as part of a delegation of Arizona tribal leaders to Washington. General O. O. Howard, pleased with the peace established, decided to bring a group of influential chiefs to meet the “Great Father” in Washington, D.C. and discuss the future of Indian policy.

In July 1872, Morago boarded a train eastward along with Chief Antonio Azul (Akimel O’otham), Tohono O’odham (Papago) sub-chief Ascensión Ríos (often spelled Accension Rios), and two Apache leaders – recorded as “Josio Pakato (Apache Yuma)” and “Carlos (Apache Mohave)”. They were accompanied by Superintendent Herman Bendell and General Howard himself. This diverse group – Pima, Papago, and Apache – symbolized a hopeful new alliance.

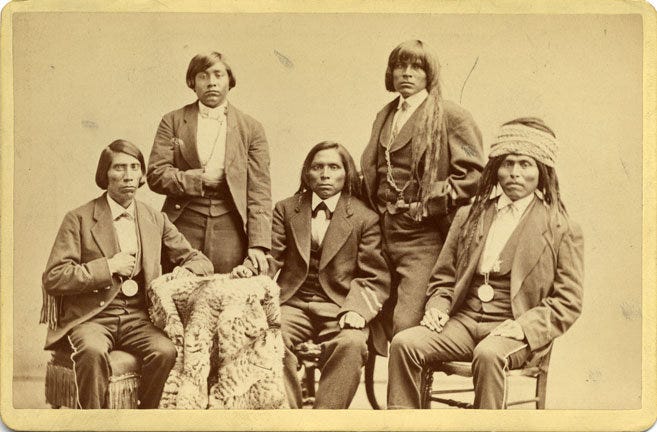

Leonard Wilson, photograph of Ascencion Rios (Papago), Unknown [likely Azul’s son] (Pima) Antonio Azul (Pima), Luis Morago (Pima), and Jose Pocati (Quechan), 1872.

Upon arriving in Washington, D.C., the delegation met with top federal officials and with President Grant. Though records of their White House meeting are few, an Albany newspaper reported their presence and noted that Dr. Bendell took the chiefs on a side trip to his hometown of Albany, New York, to sightsee. Bendell later wrote that the “chiefs showed indifference” to most sights along the Hudson River, only perking up at the grandeur of West Point.

In Washington, Morago translated as our leaders advocated for our people’s needs. Morago’s interpreting was crucial in these meetings. He would have conveyed the nuances of Azul’s requests to President Grant’s administration.

For instance, earlier that year Agent Stout had floated the idea of moving the Gila River people to “Indian Territory” (Oklahoma) due to water shortages. Azul strongly opposed any such removal and insisted on first sending scouts to inspect Oklahoma before any decision. Now in Washington, with Morago at his side, Azul could directly tell U.S. officials that our community wanted to remain on our ancestral river, and that we needed the government’s help to restore our water, not a forced relocation.

We know that President Grant was re-elected in 1872, and his Indian Peace Policy was still in effect. The presence of the Arizona delegation likely influenced federal thinking: soon after, in 1874, the San Xavier Reservation was established for the Tohono O’odham, and the San Carlos Reservation (created in late 1872) was confirmed as a home for many Apaches. These outcomes aligned with what our chiefs had urged – keeping each tribe on their ancestral lands.

The 1872 Washington delegation was a landmark in our history: it was one of the first times Akimel O’otham leaders directly addressed the U.S. government.

Irrigation and the Louis Morago Ditch (1880s)

Back in our desert home, another struggle defined Luis Morago’s later life: the fight to reclaim and preserve our water. For centuries the Akimel O’odham were master farmers, irrigating the Gila River’s waters through an extensive network of canals.

Our elders say we once dug over 500 miles of large canals, some 10 feet deep and 30 feet wide, spidering out to smaller ditches for each field Each family maintained their own lateral ditches, and we worked cooperatively to tend the main canals.

As elder George Webb remembered, “They maintained their own water system, distributing the water to anyone needing it the most. When a dam was washed out by floodwater, they all went out and put in another brush dam. When an irrigation ditch needed cleaning, they went out together with their shovels and cleaned it out.”. In those days, “as far as your eyes could see, you would see green along the river,” thanks to our communal labor and the Gila’s flow

By the late 1870s, however, upstream American settlers had diverted so much water that our crops withered. The river often ran dry through our villages. This created a crisis of hunger in our community – one that Morago experienced firsthand. Like most men in our Community, Morago used farming to feed his family.

In 1882, Agent A. H. Jackson finally provided some resources to assist us. Under his direction we constructed a major new irrigation canal on the reservation, which the agent later proudly described.

This canal would later be known as the “Louis Morago Ditch.” According to Agent Jackson’s 1883 report, our O’odham farmers cleared 75 acres for an agency farm and dug about an 8-mile irrigation canal, anchored by a substantial brush-and-log dam across the north fork of the Gila River. (The north fork, often called the “Little Gila,” was a branch of the main river.)

This new canal diverted water from the Little Gila and carried it to fields on the Sacaton Flats. We built it with our own hands, using shovels, wooden plows, and horse teams where available. Morago, then around middle-age, was at the forefront of this project. Our men labored in the desert sun, much as George Webb recalled, taking turns and helping one another.

The Louis Morago Ditch was an ambitious endeavor, but sadly within two years, the canal was carrying only a trickle. An internal agency history later noted that “after about two years of use it was found unserviceable”. Silt and low river flows had choked it.

In response, a second canal was attempted: one heading from the main Gila (“Big Gila”) across an area called The Island, designed to feed into the Morago Ditch from another angle. This second ditch also struggled, as by the mid-1880s the Gila’s waters were simply too low in most seasons.

Although the Morago Ditch did not last in its original form, it marked the beginning of a new phase of irrigation improvements that would continue into the 20th century. In fact, portions of that canal were later integrated into the 1915 Sacaton irrigation project and still have Morago’s name on maps.

Legacy and Community Memory

Morago’s exact date of walking on is not well documented (likely in the late 1890s), but his legacy lives on in multiple ways.

His family continued to serve our people. One of his sons – known as Kisto Morago – became a tribal police captain in the 1880s (Ed. date might be wrong. He was a captain, but unknown what year.) and later a community leader. In 1911, Kisto Morago co-authored a letter to the U.S. Senate Committee on Indian Affairs, alongside other leaders like Lewis D. Nelson, advocating for our water rights.

In that letter, he invoked his father’s reputation to give weight to their words, reminding officials that the Morago name had long stood for the defense of our people’s welfare. That legacy continued into the next generation—Kisto’s son, Louis Leo Morago, became a teacher and advocate in his own right, carrying forward the family’s tradition of service through education.

The “Louis Morago Ditch” remained in local memory for decades. Older farmers would refer to sections of the canal by that name for years. Even as late as the 1930s, when the federal government and our tribal council planned new irrigation works, they referenced the old Morago Ditch in their surveys. Every time water flowed (or failed to flow) in that channel, it echoed the efforts of 1882 and the man who led them.

Conclusion

Alex Gardner photograph of Luis Morago, 1872.

Luis Morago’s legacy is one of service. He served as a translator, emissary, warrior, and laborer for the well-being of others. In doing so, he helped our people navigate one of the most difficult periods we’ve ever faced.

I didn’t learn about Luis Morago growing up, and I think that’s part of the problem - we’ve lost track of so many people who helped shape who we are.

This project isn’t about making him a hero above all others. It’s about adding his name to the long list of O’odham who stood up, spoke up, and helped carry us forward. He was one of many amazing people from our history. I hope his story inspires others to dig deeper, ask questions, and learn more about the people who came before us. There’s so much to uncover and so many amazing stories to learn.

Project Summary

Like many of our ancestors, Luis Morago has never had a full biography or documentary dedicated to his life. What you’ll read here is pieced together from scattered historical documents, newspaper clippings, and federal records. It’s important to remember: always ask elders or other knowledge keepers for stories before assuming any written account tells the full truth. I’ve done my best to share what I’ve found, but there are always more stories waiting to be uncovered.

If you’re interested in reading other history content, you can find more information on my website: www.LeonardBruce.com

About 3D Printing

This project began as a 3D printing experiment - I wanted to create 3D-printed portraits of figures from our history. But as I worked on the models, I realized that the images alone weren’t enough. I wanted people to know who these individuals were and the why behind the pictures.

So I started digging deeper by doing historical research, searching old newspapers, reading federal reports, and generally trying to learn more about our history. This biography of Luis Morago is part of that larger effort: to preserve and share the stories behind the images.

This line of 3D prints was created to encourage and inspire other O’odham to explore our amazing history and learn about the people and the situations that have led us to where we are today.

You can find a 3D portrait to print for Luis Morago at my IndigeModels website page:

The file is provided under a CC-BY-NC-SA license. Print, remix, share, but don’t sell.

Other O’odham in History

Luis Morago wasn’t alone. Our history is filled with remarkable individuals—community leaders, legal advocates, culture keepers—who stood up for our rights, helped shape early tribal governance, and navigated local and federal systems to keep the Akimel O’odham strong and united. Their work laid the groundwork for where we are today.

I encourage you to create your own family profiles. Ask questions. Record oral histories. Save pictures. Share stories. Every conversation helps us understand who we are - and the more we talk, the stronger our Himdag becomes.

If you are interested in sharing a story, making corrections, or recommending a person or topic to explore you can contact me at: