Gila River’s 1901 Constitutional Draft

A reflection and analysis of a draft Akimel O'otham constitution

Introduction

(ed.

1/8/26 - Update with some corrections and updates from the esteemed Billy Allen. He made some excellent recommended edits throughout the document. But I especially want to point to the names for Juan Antonio and Antonio Azul. Billy tells me “Keep in mind these individuals were not linguists, improvising at times and more importantly-not O'odham. But with Jose Lewis and Juan Dolores, initial linguistic steps were made.” — It is important to keep in mind that most O’otham you read in older texts may be written incorrect! I’m keeping the original in since those were from People of the Middle Gilas, a they are in the historical record - but I put the corrections nearby.

9/17/25 Correction- In earlier version Solon was stated as attending Carlisle, I’ve since found he actually attended Santa Fe)

I wanted to talk about a lesser-known story from our Community about Gila River’s original draft constitution.

Most folks know about the 1936 constitution that formed our early government under the Indian Reorganization Act (IRA). Some also know about the 1964 amendments, which created the modern executive and judicial branches.

But did you know that there was an even earlier constitution, prepped and ready to pass nearly thirty years before 1936 version?

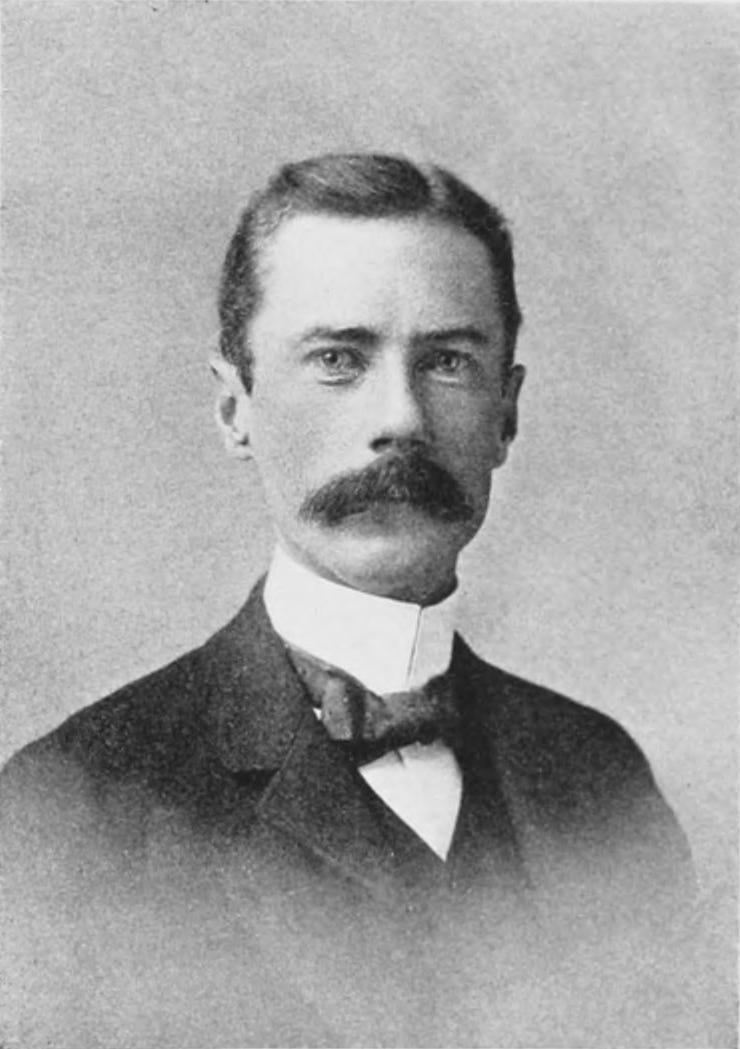

We know about this event because of the work of Frank Russell, a researcher who lived among our people around 1901 and published a paper titled A Pima Constitution in 1903.

Russell wasn’t perfect… like many early anthropologists, his writing carries the language and biases of his time: “primitive this,” “underdeveloped that.” Kind of a jerk; but, without him we might not have kept as much of our history. He passed before his research and book were published. So let’s put that aside for now.

Either way, this is an amazing article that shared part of our first recorded attempt at a written constitution. A document written by and for O’otham in the Santan District. A record of an entire system of governance based on O’otham values.

This is the story of that constitution, the people behind it, and the lessons we can learn from it today.

Setting the Stage: Chiefs, Change, and the Turn of the Century

To understand what made 1901 such a turning point, we have to go back a bit further.

Our earliest widely known chief was Juan Antonio Llunas who was known in some records as Ke:li/old man Azul; or T-a hi: tam, One who walks inside or towards, in other words doesn’t back down, physically or verbally (see edit). Juan Llunes led from around 1825 to 1855, helping guide the O’otham villages through a time of increasing pressure from Mexican, American, and tribal neighbors.

(Billy Allen Edit: Billy states that historical names Culo Azul (“Blue Asshole”), and Ti’ahiatam (“Piss”) were misheard. Corrected per his knowledge!

“Culo should be Ke:li/old man; Ti’ahiatam should be T-a hi: tam, One who walks inside or towards, in other words doesn't back down, physically or verbally”

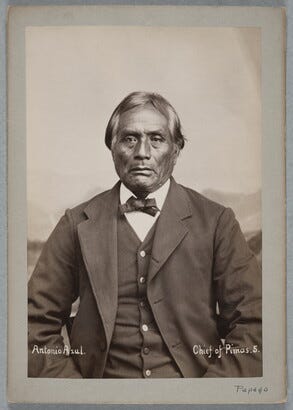

He was followed by his son, Antonio Azul, known by many names such E:da a va:ka, One who goes inside or towards, much like his father, , Ma’vit Ka’vutam (“Puma Shield”), and, in some sources, S-ce:dag m-vus, blue/green comes out from him.

(Billy Allen Edit: Billy states that the historical names Uva-a’tuka “Spread Legs”, and Ce:dagi Mus “Blue…lady parts” were also likely misheard. Corrected per his knowledge!

“Same as the father - Uva-a’tuka should be E:da a va:ka, One who goes inside or towards, much like his father. S-ce:dag Mus, I am not sure but it could have been S-ce:dag m-vus, blue/green comes out from him).”

Anyway - Azul’s time as leader saw massive shifts in our world: the Gadsden Purchase (1853) officially designated our land part of America instead of Mexico, the arrival of the first U.S. Indian agents (1859), constant warfare with Apache groups, and even the formation of Arizona’s first National Guard company (~1865) which included O’otham scouts fighting alongside the U.S. military.

Azul was noted as a leader in one of the largest victories against the Apache with the Massacre on the Gila (1857) and was part of the first peace talks with the Apache after the Camp Grant Massacre (1871). The massacre took place early in his career, he felt he was not ready for the fight, so he deferred to the older, experienced war leaders, leading to victory.

Azul helped the Community survive these storms. Under his leadership, we formed new relationships with churches and schools, and we fought off efforts to remove us to Oklahoma. He also saw our reservation created, the diversion of water from our river. He asked for schools and also accepted the Christian religion.

Around 1880, he worked with the U.S. government and Charles Cook to establish the first boarding school at Sacaton, which marked the beginning of a new era - one shaped by Western education and a new generation of O’otham youth.

Keep in mind that at the time only a sixth-grade education was available - for higher education students (including Antonio’s son Antonito) were sent to outside boarding schools like Hampton, Carlyle, and Santa Fe for further education.

By 1900, Azul had been chief for almost 50 years. He was elderly, respected, and still at the center of community life, but things had changed. A new generation of O’otham leaders educated at places like Carlisle, Santa Fe, Hampton, and Escuela began to ask hard questions about our future: What happens after Azul? Should we continue with a hereditary-style chief? Or build something new based on Western Style government.

The son of Antonio, Antonito took over but quickly realized the world had changed. Men who knew English, law and business were needed. He stepped away in 1911 and leadership was handed over to a "Business Committee”.

I don’t think this was assimilation due to colonization - our early leaders likely believed that having a more formal set of government rules would make dealing with the American government easier and allow us more power in the conversations.

The 1901 Constitution: Origins

The push for a new government came from the Santan District. According to Russell the spark came from Solon M. Jones, a Santa Fe-educated interpreter who worked at the Sacaton Agency. He shared the idea with Earl A. Whitman, who served as the disciplinarian at the Sacaton boarding school and was a graduate from Carlisle. Whitman took the lead in drafting the constitution, writing what Russell later described as a document “modeled after that of the United States.”

Jones and Whitman weren’t alone. They formed a committee with other men from the Community as well:

Antoine B. Juan (Albuquerque Indian School)

Edward Jackson (Tucson Escuela)

John K. Owens (Santa Fe)

Kisto Jackson Morago (Hampton Institute)

Oliver Wellington, who helped draft but did not formally sign

Together, they created an 18-section constitution that laid out a government that was a mixture of traditional leadership structure with western style democracy.

Head Chiefs, Headmen, and “Legs”: A Traditional Power Structure

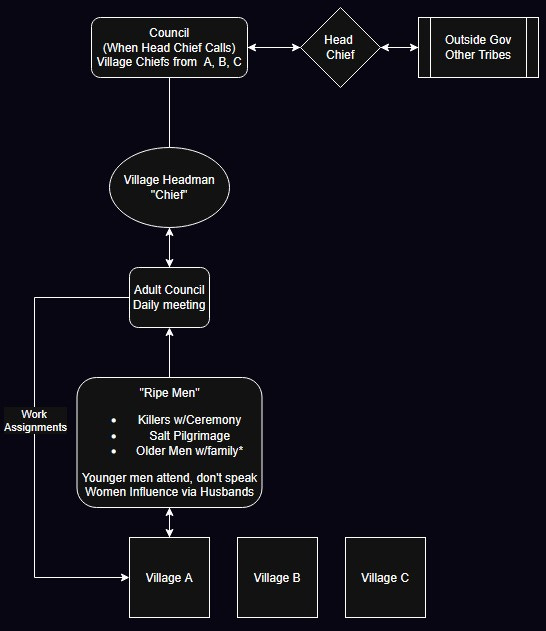

Before we dive into the constitution itself, it’s worth talking about what leadership looked like traditionally.

In O’otham tradition, power came from the people. Each village had its own headman or “chief” who was chosen by their village. These were often patriarchs of the large families who formed the villages, but it wasn’t always the oldest - the leadership often went to the most capable.

These headmen were supported by “undermen or sub-leaders," trusted helpers and organizers. These men had specialized roles and fulfilled specific duties for the headman. They coordinated everything from ceremonies to canal cleaning. Another important member was the ' leg or kahio," who delivered messages.

In Papago Woman, Chona’s father is the chief of her village and she describes some of his duties. Helping lead war parties and addressing legal challenges or conflicts with villagers. She also speaks of her father’s “legs,” describing how they helped with speeches, organizing labor, conducting ceremonies, and navigating the other needs of the people.

But the headman of the village were beholden to a council, The council meetings were open to males considered done or ripe. At meetings, only men who were “ripe” were allowed to talk and set policy. A man was considered bai or ripe when certain tasks had been performed, key was raising and caring for his family, roughly at about 30 years of age. Killers or war veterans who had gone through the cleansing rituals also earned the right to speak. Younger men were allowed to attend, but not speak. Women were not allowed to join, but it’s said they exerted power through their husbands.

Each village chief was brought together for an overall council when the Head Chief called for it - these were to discuss overall issues, but each village chief also had to follow the will of their individual councils.

Azul and his father were Headmen but didn’t have explicit control, they had soft power. They were selected and sustained for their intellect and vision, but reports say they had to lead through suasion - but consensus was the ideal.. Meaning they pointed the way and used shame or shared values to bring the Community into alignment instead of formal punishment. Villages were free to move but at the risk of an attack. There was safety in numbers.

It was a decentralized system - the Head Chief would be the face dealing with governments or other tribes, but the real power was the Headmen of the villages and the people themselves in their village councils.

It’s unclear how a Head Chief was chosen - I’ve seen some reports that it was a royal lineage, I’ve seen some saying it was based on merit and vision. O'otham; some individuals can see a long way (future), others only see today.

(Billy Allen Edit: No royalty, everyone has a gift to offer. However many felt the good qualities of the father will be present in the son. The elders watch and begin to get an idea of what each child may have to offer. See Shining Evening story in Chona. One child may be told to go gather wood, while another may be told to sit and listen.)

When Llunas passed, there was much discussion if Antonio should take the role of Head Chief - many said he was too young or didn’t have the right skills. But, he proved them wrong and was Head Chief for over 50 years!

Inside the Constitution: Building on O’otham Governance

The 1901 Santan Constitution was shaped by O’otham ways of governing that had existed for generations. These young leaders were adapting and blending village-based leadership, collective decision-making, and shared responsibilities into a formal structure that could stand up to the pressures of the new century.

Some of the ideas were adopted from church hierarchy, Protestant or Catholic. The Spaniards were looking for ONE spokesman and issued a staff, ribbon, medallion to signify the Spanish office.

Frank Russell, who published the constitution in 1903, notes that he received only a condensed version — the original was cut in half just before the meeting, likely removing 10–20 pages of content. What we’re left with is just a portion, but it still reveals a lot about their thinking.

Executive Roles

Head Chief

Elected for a 4-year term. Could call the council, enforce decisions, and refer unresolved matters to the Indian Agent. But, like traditional chiefs, he was accountable to the Council, not above it.

Assistant Chiefs (2)

Two-year terms. Tasked with communicating orders, distributing rations, and appointing local helpers.

Undermen

Head Chief appointed aides, similar to the traditional “legs” that supported headmen in local organizing, speech-making, and work coordination.

Minute Men

Oversaw canal and dam labor, reporting to the Undermen. A new name, but a role that matches traditional ditch tenders and irrigation labor coordinators in traditional village structures.

Legislative Roles (The Council Remains Central)

Council of 11 members

Made up of 8 elected Councilmen, 2 Assistant Chiefs, and the Head Chief.

Annual rotation

One-fourth of the Council elected each year - a system designed to balance community accountability with stable leadership.

Powers of the Council

Responsible for all general issues, settling disputes, reviewing fines, and directing the Head Chief on what to enforce.

Infrastructure and Resource Management (Canals, Roads, and Labor)

President of the Canal

Elected to oversee all dam and water distribution. Although it’s unclear who they reported to, this role resembles the traditional “water captain” or “Alcalde", who organized irrigation and work crews.

Water Directors

Appointed by village Chiefs. These local managers likely reflected the ditch tenders who helped organize water use by section.

Road Overseer

Appointed by the Head Chief. Managed public road repair and enforced labor participation. Failure to help with road work resulted in a fine - a formalized version of the public duty requirements that existed in the villages.

Work like ditch repair or irrigation were shared responsibilities. Road repair was relatively new to the Community, but followed similar rules. The constitution preserved this ethic but added formal rules and penalties to strengthen participation and fairness

Local Laws and Civic Obligations

Livestock trespass rules

Animals caught in someone’s field could lead to fines. This ended up being a major sore point for Antonio Azul, who had many free-roaming cattle.

Fence and gate regulations

Required maintenance of fences and gates, and imposed penalties for damage or neglect.

Ditch labor requirements

Men were required to show up for canal repair unless excused. Substitutes were allowed, but skipping work without reason resulted in a fine.

Environmental responsibility

The constitution prohibited irrigating uncultivated land — a surprising but wise move, ensuring that limited water only went to active farms.

A Cultural Translation

Some might see this as the beginning of Western-style government in Gila River. But when you compare it to what we know about traditional O’otham governance, it becomes clear that this matches the traditional governance system of the O’otham in a new light.

The Chief and Council worked together, just like Head Chief and Village Chiefs did in the past.

Water systems were communally managed, with roles for elected and appointed positions.

Public labor and civic duties were expected, not optional.

These men were creating something both new and timeless. We can see elements of our traditional structures being paired with Milgan style government in an attempt to strengthen both.

What is funny to me is the critique by Russell who complains that the document is crude and incomplete, but if he had known more about our traditional structure of government I think he would realize this was a very amazing attempt to modernize O’otham governance to meet the needs of the day.

What’s Not in It

I think what is also interesting is the stuff that is not in this draft of the constitution….

There are no blood quantum requirements or enrollment rules in this constitution. No roll numbers, no percentages, no categories of “full” or “half.” At a time when the federal government was pushing blood quantum as a tool to limit tribal citizenship over generations, the authors of this constitution didn’t touch on the idea.

People were part of the community because they lived it, contributed to it, and were raised in its responsibilities. Maybe it was a simpler time, but I think the idea that identity could be fractionalized would have made no sense to our ancestors.

(Billy Allen Edit: This comes from the code of warriors; never kill children or women. They were to be taken captive and brought back to the village to become a slave, taking the place of one who had died or killed. Most were allowed their freedom much later on.

We were a crossroads, a trading center with other Natives coming in from all directions. The blood of many groups is in our veins.)

There’s also no mention of U.S. citizenship, allegiance, or dependency. This is especially striking because by 1901, many boarding school-educated Native youth were being encouraged to embrace U.S. citizenship as a mark of “progress.” Yet here, these young leaders chose not to center their identity around that. They weren’t trying to “become American.” They were building something for their people to continue their traditional governance.

(Billy Allen Edit: US Citizenship didn’t come until later in 1926 with the Indian Citizenship Act of 1924. O’otham were not allowed to vote until much later.

In 1928, two Gila River tribal members, Peter Porter and Rudolf Johnson, filed suit for the right to vote in elections. They were denied.

Harry Austin and Frank Harrison of Fort McDowell finally won a court case in 1948, but true voting rights were not obtained until the Voting Rights Act of 1965 outlawed literacy tests and other discriminatory practices.)

Collapse and Aftermath: What Went Wrong

So what happened? Why don’t we still have a Head Chief and folks don’t know this story?

Well, the constitution was submitted to the Indian Agent, who approved it. A public meeting was held, and about fifty O’otham gathered to adopt it. John Lewis of Santan - a respected leader, and veteran of the apache wars - was elected Head Chief under the new system.

By all appearances, the transition had succeeded.

But then came the backlash.

One of the ex-Carlisle men reportedly upset he wasn’t chosen as chief complained to the Indian Agent. At the same time, Antonio Azul, still alive and politically powerful, objected to the constitution as well. The livestock provisions specifically would have affected him personally, as he owned many free-roaming cattle. Him and some of his followers criticized the new constitution.

Under pressure, the Indian Agent withdrew his approval. The system was vetoed.

John Lewis resigned, stating that he wanted the constitution to succeed, but would not serve without full community support. The moment Lewis chose unity over power was the end of the effort.

The constitutional committee continued to hold meetings, but there wasn’t a successful push to form a new government until the IRA-constitution in 1936.

Comparison to the 1936 Constitution

Yep - it would be ~35 more years before Gila River formally adopted another written constitution under the Indian Reorganization Act (IRA) of 1934.

That federal law was framed as offering tribes the chance to form recognized governments. But with that offer came a federal template that didn’t emerge from our Community’s traditions. While we were not forced to adopt the federal template, we know now that there were extreme pressures placed upon leaders at the time to follow the template as closely as possible.

Our 1936 constitution followed that template more than it reflected O’otham governance.

It established a strong legislative council, modeled on congressional systems, but it eliminated the role of Head Chief. Unlike the 1901 version, which gave a clear executive function to a community-selected leader, the 1936 document didn’t include an executive branch. Instead, administrative power, including the position of Governor, was a position selected from within the Council itself, blurring the line between legislative and executive authority.

We didn’t have a strong executive branch until the amendments in the 1960’s when a descendant of Luis and Kisto Morago, Jay R. Morago, spearheaded a campaign to include the role in the constitution.

It introduced bureaucratic membership rules: enrollment numbers, blood quantum requirements, and legal definitions of who counted. These systems were not part of O’otham ways of belonging, but became official policy. They sometimes excluding families who had always been part of the land and community and we still are dealing with those issues today.

It also formalized federal oversight, with requirements for BIA approval of actions, strict rules around ordinances and resolutions, and outside auditing of tribal decisions. In practice, this often meant that while we had a formal government, we didn’t always have full control over it.

It’s also important to note that even in 1936, not everyone supported the new constitution. In papers like the Chick Pan, some voices raised concern that the IRA document was just another way for the federal government to tighten its grip on tribal affairs and that the new system might weaken our own internal forms of accountability. That’s a different story, for a different article. But it’s a reminder that every constitution came with its own tensions and compromises.

Conclusion

In 1901, in the Santan District, a group of young O’otham leaders didn’t wait for permission. They drafted a constitution. They gathered the people. They organized elections.

This moment pushes back on so many of the tired narratives about Indigenous peoples. It shows that we were not broken, defeated, or passive. Even as federal systems tried to mold us through boarding schools, land policies, and religious pressure, our people were already using those same systems to serve our needs. We sent our children to learn in those schools not to become white, but to come back and lead. And they did.

The Santan Constitution wasn’t a copy of the U.S. model or created from a forced template. It was a grassroots hybrid rooted in our cultural history.

The people behind it - Solon Jones, Earl Whitman, Kisto Morago, John Lewis, and many others went on to serve as nation-builders in the decades that followed.

Maybe one day, future generations will look back on our time and see the same pattern. That even in a time of language loss, cultural disconnection, and change, we are still evolving, still adapting, still finding ways to carry O’otham values forward. That just like these young leaders in 1901, we are working to keep our history and culture alive for what’s still to come.

If you made it to the end, thanks for reading and subscribe if you are interested in content like this. I’m working on a biographical sketch of the folks who were signatories of the constitution. If you or someone you know is family or know any of these folks I’d love to get more information on them. You can contact me at LFNBRUCIE@gmail.com

And - if you want even MORE reading, I grabbed much of my knowledge from: