A Brief History of GRIC Newspapers

“From the Chick Pan to GRIN: Nearly a Century of Community Journalism”

*You can find this project HERE

You may be familiar with my work on developing the Gila River News Database - a project that led me into researching a few of the publications of our Community.

This is a companion piece I wrote because I wanted share some context about our different community papers and pass along what I’ve learned from reading them—along with tidbits from archivists and elders I’ve met during this project. I’ll also note there are lots of other papers that I missed - the St. Johns School Thunderbird comes to mind for instance. But, these are the papers I’ve been able to find and record.

I’ll say up front: I’m doing my best with the sources I’ve been able to find so far. I’m not 100% certain on every detail, but maybe some of it will resonate or help you learn more.

Skoek Oidak Chick Pan: ~1930

Good Farm Work. The Beginning. The first paper I’ve been able to find for Gila River.

As I understand it, the Chick Pan was create in ~1930. Here is a blurb that was published in the last issue in 1942. It was a re-publication of the first paragraph from the first paper in 1930:

It’s hard to read, but the first issue says the paper was named by Tom Blackwater, Henry Enos, and Johnson Jackson. It was published by the Indian Field Service under the Department of the Interior—basically through the Indian Agent or Superintendent at the time.

The paper was originally created to deliver news and information to farmers—hence the name. But over time, it grew into something much more.

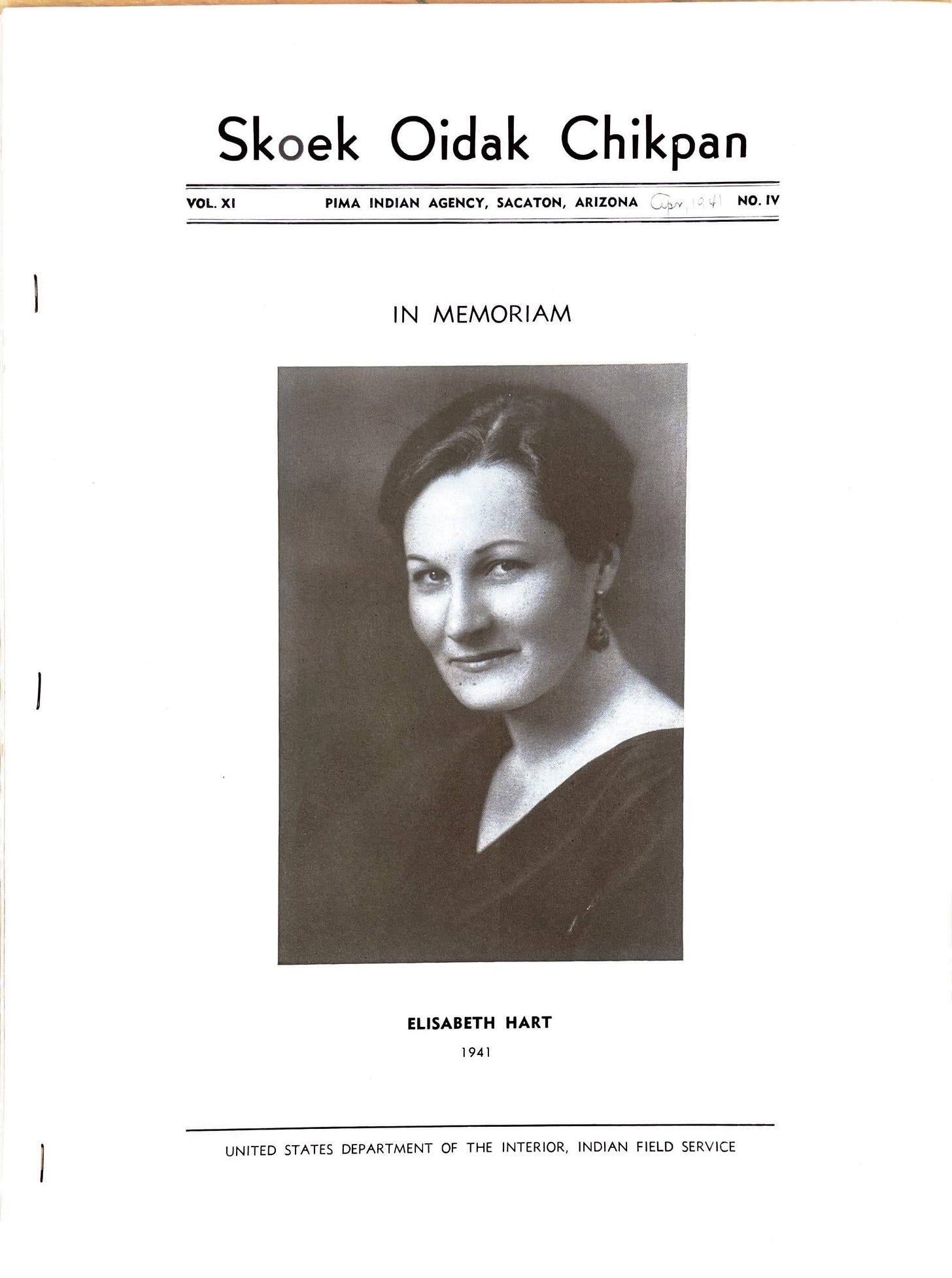

I don’t have access to the earliest issues, but a clear shift shows up in the editions I have read, starting when Elisabeth Hart arrived in the Community in 1934. I think she played a major role in developing community-run news.

Elisabeth served as the Home Improvement Officer—basically the woman the federal government sent in to teach domestic life skills. A lot of the programs she ran focused on things like sewing, cooking, and home care. There’s a whole, excellent book about women’s clubs and the home extension service that gets into this more deeply, but I won’t go too far here.

What stands out is that, beyond the usual federal agenda, Elisabeth really connected with the women in the Community. She helped establish women’s clubs in villages across the Pima Agency—including Gila River, Salt River, Ak-Chin, and others. Eventually, more than 400 women were involved in her programs. Part of that work included organizing regular village news updates from the different clubs. In the paper, there are several mentions of her asking for club leaders to identify themselves and submit news by specific deadlines.

There are multiple references in the papers to Elisabeth requesting the names of each club’s leader and setting deadlines for them to submit their village news.

We also know the Community held her in high regard. Elisabeth tragically passed away young, in 1941. After her death, the Home Extension Council—yes, the women of the Community had their own group, with regular meetings and a leadership structure—gathered and dedicated an entire issue of the Chick Pan to her memory.

Unfortunately, the paper changed after her passing. It’s clear that her absence had an impact, and not long after, in 1942, the Chick Pan was discontinued.

The official story is that the paper had simply run its course. A.E. Robinson, the Superintendent at the time, wrote in the final issue that the reason for ending the paper was the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor. The issue published after the attack, in January, was the last one. He claimed that shortages and the need to focus all efforts on the war made it impossible to continue.

But if you look closely, especially when you compare it to what continued in the Pima Central Gazette, you’ll notice that those same reasons didn’t stop other publications during that time.

I think the real reason the Chick Pan ended was because of Hart’s passing. Without someone who cared enough to gather news and updates from the community, the agency no longer had the motivation or commitment to keep it going. Her death gave Robinson and the Indian Agency a convenient excuse to shut down public news.

Still, this was the first community paper—at least the earliest I’ve been able to find. It contains incredible stories from that time. The passing of our first constitution. Debates over Operations and Maintenance (O&M) for our water settlement. The creation of our first tribal laws. There’s even a copy of our first dance ordinance, which you know I love to explore.

But more than the news, the Chick Pan holds countless personal stories about everyday life. Stories from the villages, of people just living. One of them is about my great-grandfather, John Ramon, and how he gathered family to help thresh his wheat. There are stories about the leaders of that time, and about the people who would go on to become leaders in the future.

It’s an amazing look at our history.

The Pima Gazette: ~1935

This paper started a bit later than the Chick Pan and was published out of Pima Central High School in about 1935

Oh, what? You didn’t realize we had a high school in the 1930s? Don’t worry—you’re not alone. A lot of folks have forgotten that the Pima Day School next to the old District 3 Service Center used to be more than just K–6 or K–8. It was once a high school.

And not just any high school—Pima Central was one of the first under the Federal Government’s Day School Plan, launched around 1930.

Before talking about the newspaper, it’s important to understand the nature of the school itself.

Imagine this: schools had existed in Sacaton since around 1880, but they were primarily boarding schools. Children were taken from their homes and lived full-time in these residential schools in Sacaton through about sixth grade. After that, they were sent to boarding schools outside the community—most often to Carlisle (in Pennsylvania), Sherman Institute in California, or Escuela in Tucson.

Yes, all the stories you hear about boarding school experiences are real. Even back then, the federal government had reports acknowledging the terrible conditions many children endured. One of the most important was the 1928 Meriam Report, which documented the overcrowding, malnutrition, and emotional harm found in boarding schools across the country. It concluded that the treatment of Native children was “grossly inadequate.” Reports like this helped push the government toward a new approach: day schools. Instead of removing children entirely, the idea was that they could live at home and attend school during the day.

So, in 1928, the tribe received a number of day schools.

That shift brought a big change—and honestly, it must have been a shock for families. For nearly 40 years, kids were being sent away from home for most of their childhood. Now, suddenly, they were back—living at home full time, and their parents were once again fully responsible for them. A romantic idea in theory, but the adjustment must have been hard. That’s a subject worth exploring on its own another time.

As part of this new plan, the federal government also aimed to bring high school education back into tribal communities. The goal was to offer a full K–12 education without separating kids from their families. Still, many parents chose to send their children to schools outside the Community. For example, Ira Hayes began his freshman year at Pima Central but later transferred to the Phoenix Indian School.

And then came the Pima Central High School

At the time, the school system across Gila River served about 900 students, spread out across various day schools in different districts. But the high school itself—Pima Central High School—was relatively small. It had only about 20 to 30 students across all four grades, from freshman to senior. Still, its existence was a major achievement. For the first time, students could stay at home and attend high school while remaining connected to family, community, and culture.

And the students did some amazing stuff - for the duration of the Gazette it was written and edited by the students. Each of the stories is written by a student reporter, and it was an amazing effort to bring information about the lives of each child and their families into the paper. Even when WWII was raging and the Chick Pan stopped publishing, the Gazette continued on.

In addition to the amazing work they did to publish the Gazette, PCHS also had the distinction of graduating the first class of Native American high school seniors in the entire country. These students were the first to complete their education while living at home, rather than being sent away to boarding schools. Gila River was leading the way.

The school lasted about 10 to 12 years. Based on what I’ve been able to gather, the first issue of their student newspaper was published around 1935, and the final issue came out around 1946. If you’ve read the story about how I came across these issues, you know there’s a chance that more are buried somewhere—maybe even lost in a landfill. But digging through the history books suggests my hunch is right: the high school seems to have closed for good around 1946 or 1947.

From what I understand, Superintendent A.E. Robinson made the decision to shut down the high school and instead bus students to nearby public schools. And just like that, this short but important chapter in Gila River’s educational history came to a close. Still, we have elders in the community who remember stories from their family about attending the school. And we have the Pima Central Gazette as proof they were there.

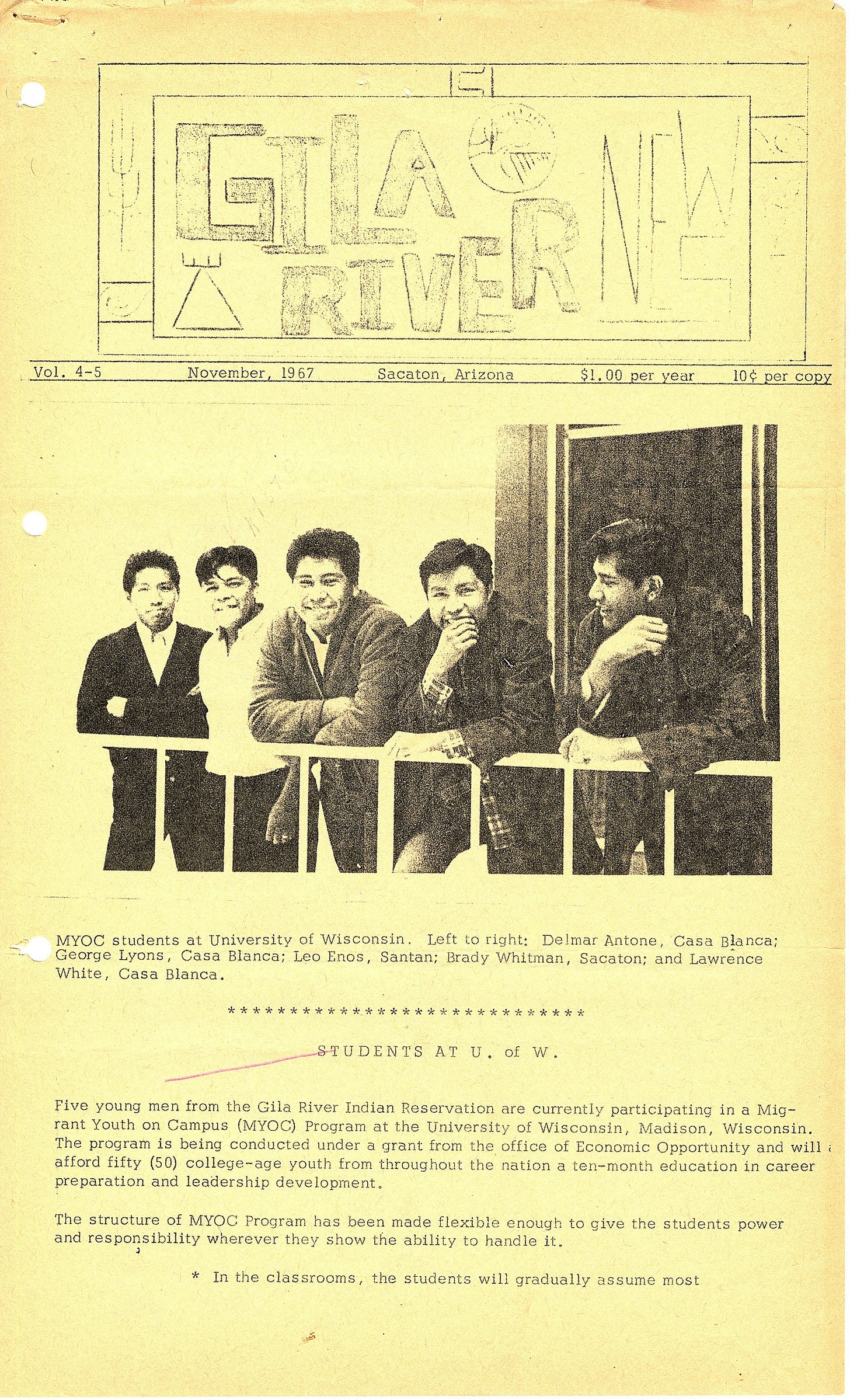

The Gila River News: ~1964

The Gila River News was the first newspaper published under our modern tribal government—starting around 1964. This one’s a bit easier to trace because, thankfully, there are a few “history of the paper” writeups inside the paper itself. So we actually have a pretty clear origin story to work from.

Here’s the basics:

The paper officially launched in July 1964 as a grassroots effort to create a space for self-representation and community communication. A lot of different people and groups came together to make it happen:

Students from Casa Grande Union High School and their teacher, Guy Acuff, wanted a journalism outlet that focused on news from the Reservation.

Folks at the local BIA office—especially Wayne Baskin—were looking for a way to share updates through print.

Tribal elders remembered earlier papers and wanted something like that again. One name that comes up a lot is Bertha Parkhurst, a teacher who helped get things moving.

And the Tribal Council saw the paper as a way to rebuild pride and reconnect people to their heritage.

To get it off the ground, the Public Health Service (PHS), Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA), and the Tribal Council all pitched in. Each contributed a third of the materials—paper, ink, supplies—which funded the first four months of free distribution.

And here’s what’s wild: the paper was completely volunteer-run. Everyone pitched in—from the editors to the typists to the kids licking stamps. They even made shared meals during the long work sessions, supported later on by subscription revenue. Each issue took an estimated 200 hours of volunteer time. That’s over 7,000 hours in the first three years alone.

By the end of 1964, the paper had about 300 subscribers. That number quickly grew to nearly 600. At first, it had ads, but eventually they shifted to a no-advertising model, relying just on subscriptions and community support.

So, what kind of stuff did the paper actually include? Here’s a quick list of regular content:

Tribal Council updates

Community Action Program news

Health education from PHS

BIA department updates

School notes from students in Coolidge and Casa Grande

District news from across the reservation

What stood out to me as I read through these papers is how much they followed the format of the Chick Pan and the Pima Gazette. Yes, there were official updates and big-picture news, but a lot of the paper was focused on local stories—what was happening in the villages, who was visiting, who got a new job, who went off to school. It was personal and community-driven.

Now, while people like Guy Acuff and Bertha Parkhurst played a big role in getting the paper started, I don’t want to forget about Alexander Lewis Sr. He was the Lieutenant Governor at the time and served as the first editor of the paper. He later became Governor and left a major mark on both the paper and the Community.

One of the standout stories that the Gila River News followed closely was the Vh-Thaw-Hup-Ea-Ju initiative. This was an economic development plan first introduced in May 1966. The name roughly translates to “We are going to do it (again),” and it represented a powerful shift toward self-determined economic planning. I could probably write a whole separate piece on that project—it was a bold, community-driven vision for growth coming out of our new constitution and new leadership.

The paper covered the project in depth, including updates, meeting notes, and even a detailed report from the University of Arizona’s School of Business in October 1966. It was clear that the newspaper saw itself as more than just a place for announcements—it was there to inform, connect, and support a growing sense of purpose and unity in the Community.

And it wasn’t just the big stories. So many of the smaller community updates—births, school awards, potlucks, community celebrations—are incredibly valuable. They give us a window into the daily lives of our families and ancestors. If you haven’t already, I highly recommend checking them out.

The Gila River News didn’t last long—its final issue was in November 1970—so just about six years. But it packed a lot into that short run. It’s a great example of how the Community stepped up to stay connected, tell its own stories, and lay the groundwork for the papers that came later.

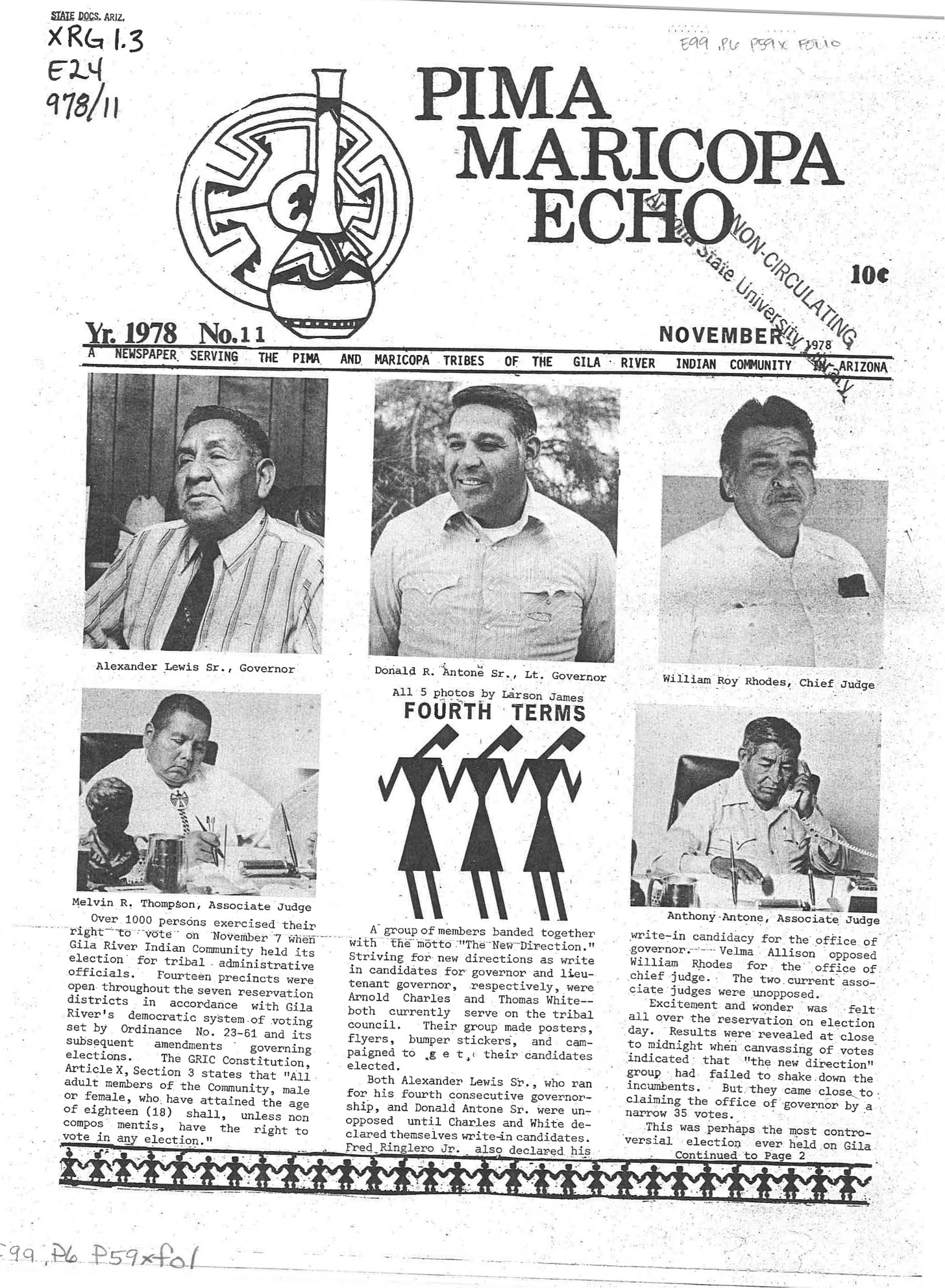

The Pima-Maricopa Echo: ~1971

After the Gila River News wrapped up, another paper stepped in to carry the torch. The Pima-Maricopa Echo started in January 1971.

I don’t have a full origin story for this one, but from what I can tell, it was published through a collaboration between the Gila River Indian Community and the Casa Grande Dispatch. I’m not totally sure why the Community gave up some level of control over the paper—maybe it was to have a more independent editor, or maybe just to modernize the layout and get access to better printing equipment. It might’ve been a natural upgrade from the mostly volunteer-run Gila River News.

Whatever the reason, what’s clear from the staff lists is that a lot of Community members still worked on the paper. And from what I’ve read, most of the editorial control still rested with the Community—almost all of the stories are focused on Gila River news.

That said, there was a shift in tone.

One of the big differences is that there were far fewer local village updates. The Echo marks the moment when the paper shifted toward covering “newsworthy” stories—things that were broader in scope and more aligned with traditional news values. You don’t see as many personal stories, wedding announcements, or notes about who was visiting from which district.

It still makes for interesting reading, but I think the paper loses some of the charm and personalized feeling that the Chick Pan, Pima Gazette, and early Gila River News had.

Even so, there are some amazing stories in the decade or so that the Echo ran. Just a few highlights:

The campaign of Georgette Chase, the first woman to run for Governor of Gila River

The development of the Career Center in Sacaton

A ton of reading and writing lessons for both Pee Posh and O’odham languages

Regular coverage of major infrastructure and governance efforts—like the tribe’s first EPA grants, covering water protection, pesticide use, and other environmental concerns

The rise of FM-4, an early technology and manufacturing company partially GRIC-owned and based in Lone Butte

The appointment of the first O’odham BIA Agent, Edmund Thompson

And—one of my favorite recurring features—Neil’s Corner, a regular column by (I believe) Neil Banketewa, where he wrote about everything from MMIW to economic issues to personal reflections on community life

Another standout moment from the Echo is the debate over whether Snaketown should be turned into a national park. There was a serious push in the 1970s to develop the archaeological site into a federally recognized park. The newspaper captured a fascinating back-and-forth between community members: in 1976, Alberta Lopez wrote a letter strongly supporting the idea, highlighting the cultural and historical value of the site. Then in 1978, Raymond Cawker wrote a response letter laying out why the land shouldn’t be turned into a park at all.

That exchange is such a great example of what makes these papers valuable—it’s not just news, it’s a record of the conversations our Community was having about its future.

The Echo ran until June 1982. After that, it was a couple of years until we got the Gila River Indian News that we still know today!

The Gila River Indian News (Part One and Part Two): ~1985, ~1998

The first issue of the Gila River Indian News (GRIN) was published in August 1985. That first front page included a letter from the Governor welcoming readers to the new paper.

I haven’t been able to do a deep dive of those early issues to confirm all the details, but from what I understand, the push to launch this paper under the Community’s direction was about one thing: control. This was about Gila River having full control over the news being created and shared with its people.

Woo, sovereignty.

In the beginning, even though the paper was under Community direction, the staff was still contracted. The editor and other team members weren’t full government employees, and they had some independence in shaping the content and tone of the paper. This version of GRIN lasted for about 13 years.

Around 1998, there was a major shift. Governor Mary Thomas, from what I’ve gathered, made the move to bring the paper fully under tribal government control. A new department was created within the government, and from then on, the paper became a direct arm of the administration.

I see the moment as a turning point for local news in our Community. Maybe I’ll be proven wrong, but bringing the paper fully under tribal government control marked the shift toward what feels like a more filtered and cautious publication. There are still good stories — meaningful features, cultural pieces, and strong reporting — but some of the harder conversations seem to be missing. The kind of deep questions or community critiques that used to show up don’t seem to make it to print anymore.

To be fair, the paper still carries some independence. But after reading hundreds of issues from our earlier papers, it’s hard not to feel like something’s been lost. The tone is more careful now. And while I’m grateful the paper continues, I miss the open dialogue and the raw, sometimes messy reports and community letters we used to see.

Still, what is incredible is that the Gila River Indian News has continued publishing for nearly 40 years! That’s an incredible streak of continuous local news coverage.

And the paper still serves an important role. It’s often the only place to find out about community events, government updates, and things like new buildings or infrastructure. It’s also the place where Council Action Sheets are published, giving us a record of decisions that shape our government and daily lives.

Unfortunately, a lot of what once made the paper feel personal has faded. Letters from Community members are rare now. Editorials and opinion pieces are almost nonexistent. I hope we see a return of village-centered reporting and more opportunities for members to share their voices.

Wrapping Up - Looking Forward

It’s also worth stepping back and seeing the bigger picture. Local news isn’t just changing in Gila River — it’s struggling everywhere. Across the country, papers are shutting down, subscriber numbers are falling, and more and more local outlets are getting swallowed up by regional or national media. It’s getting harder to find truly local reporting — something created by and for the people who live in a place.

That loss matters. Without local stories, communities start to disappear from the record. If we didn’t have those early papers—the Chick Pan, the Gazette, the Echo—would the Arizona Republic have told the stories of our ancestors? Probably not.

That’s why I’m hopeful about what’s emerging now. There’s a wave of independent creators using social media to report, reflect, and reconnect. I think that’s powerful. It brings back the grassroots energy of those early papers. But we also need to be careful not to rely only on scattered voices. We still need a central space—a shared platform where our stories can live side by side. Even if it’s not perfect. Even if it’s not always independent. Having a central story for our Community is a powerful and important part of our history.

A Note on AI

I also want to add a note on AI. It’s already creeping into newsrooms, and we know it’s going to be part of the future. And honestly—I think that’s okay. I use it myself. It can be a great tool to brainstorm, draft, or organize. But it should support journalism, not replace it.

We still need real people who know the Community. Reporters who know our history, who speak with our elders, who understand the weight of what gets written and what doesn’t. We need journalists and editors with roots here—who show up, ask questions, and care.

Final Thoughts

I do wish the paper today took more risks. That it talked more openly about the issues we face—poverty, addiction, violence. I wish it pushed a little harder to hold leadership accountable and show us not just what’s happening, but where we’re going.

But, I’m still grateful we have something. Because 100 years from now, someone might pull out an old issue of GRIN and find their family, their district, their story. They might find themselves.

And that—imperfect as it may be—is one of the strongest tools we have for building sovereignty.

Closing This Chapter

Looking back at the history of our newspapers—from the Chick Pan and Pima Gazette, to the Echo and GRIN—what stands out most isn’t just the headlines. It’s the people behind them. The students, elders, volunteers, and staff who kept showing up to tell the story of our Community. Even when the tools were limited. Even when the funding was tight. Even when it meant licking stamps and folding pages by hand.

Each paper reflected its time. Some were handmade and grassroots. Others more formal and institutional. But all of them mattered. They tell our stories, mark our milestones, and record the lives we live.

That’s what this project is about—making sure those stories don’t get lost. Making sure we keep showing up to tell them. And making sure our future generations can look back and see themselves in the record.

This is just one piece of the work. There’s still more to find, more to digitize, more to understand. But I hope this history shows just how powerful it is to tell our own stories—and how much stronger we are when we do!